Pharmacy Choice White Paper

INTRODUCTION

Managing workplace injury pain can be an arduous task for medical providers, patients, and researchers alike as the spectrum of treatment is complex, with several factors to consider for each patient. To accommodate individualized treatment, the field of pain management continues to expand access to non-pharmacological options and opioid alternatives while navigating the intricacies of state and federal regulatory environments. However, even as advances in the field are evolving, they can, at times, be limited in their capacity.

Non-opioid pharmacological options in workers’ compensation commonly include, but are not limited to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, i.e. Motrin, Advil), dermatological agents (topicals such as creams, ointments, gels), acetaminophen (Tylenol), cortisone injections and gabapentinoids, which relieve pain for particular conditions in the nervous system. Whereas non-pharmacological options may comprise of physical therapy (PT), acupuncture, spinal cord stimulation, and electric signal therapy. PT is much more apparent in the workers' compensation space as a non-pharmacologic alternative with efficacy data more widely available.

Workplace injuries can happen in any industry, even for remote workers. Nevertheless, there are a few industries considered high risk where work-related injuries occur more often. Per the Bureau of Labor Statistics (i), these fields of work include construction, warehousing, transportation and various agricultural occupations. Although, industries may vary in their workplace injury occurrence, the top work injuries keeping workers off the job, according to the National Safety Council (ii), include:

a.) Sprain, strains, and tears

b.) Soreness and subsequent pain

c.) Cuts, lacerations, punctures

Common injuries resulting in lost workdays consist of:

a.) Overexertion (i.e. lifting, lowering, repetitive motion)

b.) Contact with objects & equipment (ie. struck by object/equipment, caught in equipment)

c.) Slips, trips, and falls (i.e. falling to a lower level)

Many of these injuries result in pain to the injured worker. Those suffering such injuries will usually meet recovery standards, regrettably others may experience pain that lasts for months, if not years. These patients that endure longer-term pain are categorized as the one out of every six (iii) Americans with chronic pain.

Definitions of chronic pain can vary amongst the medical community. Most practitioners generally view chronic pain as pain lasting three months (iv) or more (v) . Chronic pain holds a wide range of conditions, with spouts of pain staying as little as three months to indefinitely. Intractable pain is on the more severe side of the chronic pain spectrum. The condition of intractable pain is considered pain that is not only chronic but unresponsive to traditional treatment. As the subject of intractable pain continues to be comprehensively reviewed states have taken on different definitions. It is suggested that high-impact chronic pain including intractable pain affects 7.4 percent (vi) of the population with varying severities and is associated more with Americans who live in more rural areas.

With the field of pain management expanding to new therapies, injured workers today have more options at their disposal than ever before. Experimentation such as the emergence of stem cell therapy (vii) is pushing the boundaries of pain management study with novel techniques in treatment being developed and perfected. Although, until these innovations make their way through proper channels and federal clinical clearance, injured workers will have little choice but depend on mainstream routes to cope with their pain.

SHIFTS IN WORKERS' COMPENSATION PAIN MANAGEMENT

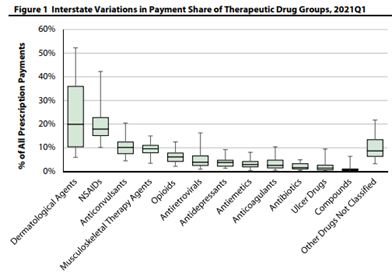

Analyzing claims from 2018 through 2021, dermatological agents such as topicals (creams, gels ointments) comprised on average, 20 percent of a state's workers' compensation prescription payments, the highest of all drug categories. Meanwhile, NSAIDs made up around 18 (viii) percent of all prescription payments on average. In states such as California NSAIDs were more than one-third (ix) of all drugs dispensed. Meanwhile anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin, encompassed approximately ten percent of a state's prescription payments. From 2015 to the first quarter of 2021, topicals saw a 10 point uptick (x) in payment share, indicating the possibility of greater use of dermatological agents in workers' compensation. The same trend can be witnessed NSAIDs with more moderate increases.

Workers' Compensation Research Institute (WCRI) June 2022

Medical Cannabis

Medical cannabis is also an option for those struggling with mainstream approaches. The substance shows improvement in a variety of pain symptoms. In addition, a peer-reviewed University of Michigan study (xi) revealed a 64 percent reduction in opioid use amongst chronic pain patients utilizing medical marijuana. Multiple studies have demonstrated a variety of positive developments in pain patients who use medical cannabis. Cancer patients and those undergoing chemotherapy, in particular, have seen significant improvements in symptom relief of 30 percent (xii) or more. Currently, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration gives its seal of approval to one cannabis-derived drug and three cannabis-related drug products, showing that cannabis-based treatments will likely play a future role in pain management.

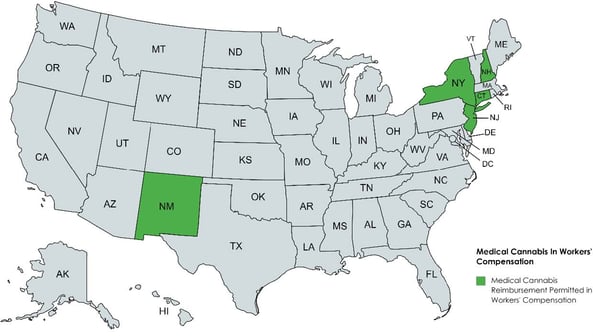

While medical marijuana is somewhat effective in mitigating the pain of those with certain chronic illnesses and cancer, it is clinically less helpful (xiii) in treating acute pain, seizures, and certain inflammatory diseases. According to available studies, the plant-derived substance is shown only to treat certain conditions. There is also a plethora of regulatory and clinical (xiv) roadblocks to medical cannabis. As the substance is still considered a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), several providers are cautious about prescribing medical cannabis in workers' compensation. For those practitioners who recommend medical cannabis, reimbursement from a workers' compensation carrier for such treatment is an obstacle. Despite most states having medical marijuana programs in place and an increased number of states fully legalizing recreational use, only a handful of states allow reimbursement of medical cannabis for workers' compensation injuries, such as Connecticut, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, and New York. The U.S. Supreme Court's decision not to hear the issue, signals that individual states will continue to take their own approach to reimbursement of medical cannabis in workers' compensation.

The rise in non-opioid medications and treatment options come at the same time opioid use, and payments are significantly declining in workers' compensation. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) reports that workers' compensation claims with at least one prescription for opioids have witnessed a 55 percent decline (xv) since 2012. Since 2018 per claim payments for opioids have decreased by 56 percent (viii) in the typical state.

Nonpharmacologic options, such as physical therapy, do provide another avenue for injured workers to explore. Some of those hurt on the job may even use physical therapy in conjunction with prescribed medicines to speed up or enhance recovery. However, timing is vital for injured workers if choosing physical therapy (PT). The Workers' Compensation Research Institute (WCRI) indicates that those starting PT early in their injury have better general outcomes and quicker recoveries. In contrast, the institute found that weeks of temporary disability per claim were 58 percent (xvi) longer for those commencing PT 30 days or more after injury. Overall, PT is shown to improve (xvii) recovery and shorten temporary disability duration if treatment begins quickly after injury. Unfortunately, a workers' compensation claim, more often than not, will take time, lessening the chance of starting proper PT services within 30 days of the post-injury timeline.

A new shift to non-opioid alternatives and non-pharmacological options is steadily becoming the norm in workers' compensation. This progression shows the industry's willingness to evolve and provide increased opportunities to care for injured workers in their quality of care.

ADDRESSING THE NEEDS OF CHRONIC & INTRACTABLE PAIN PATIENTS

Promising modernized therapies and alternatives are slowly but surely making their way to the mainstream in years to come. Until then, pain management advocates say chronic and intractable pain patients are at the present moment, left with little relief for their pain. For some dealing with chronic and intractable pain, who have attempted numerous therapies without success, clinically supervised opioid therapy may be the only path to find some reprieve from their pain symptoms. However, numerous injured workers dealing with chronic pain struggle to gain access to such medications that allow them to function for daily activities and provide some type of normalcy.

Center for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines released in 2016 (xviii), while well-intentioned to reduce opioid prescribing to the general population, have adversely impacted chronic and intractable pain patients access. The guidelines called for stringent limits on opioid access, dosage, and even tapering. Such constraints have created a sense of fear for prescribers and heightened liability, producing a clinical environment inhospitable to chronic pain patients, leaving many to deal with their pain among limited resources.

Despite good faith efforts to get a hold of the opioid crisis by regulators, the guidance inadvertently punished those who found opioid treatment as one of their only solutions to managing pain. Ridden with daily chronic pain, many have seen their treatments disrupted and filled with obstacles, only delaying care. The National Pain Advocacy Center warns that more than 50 percent (xix) of doctor’s won’t see a patient who manages pain using opioids and 81 percent were “reluctant” to. A 2018 American Cancer Society research poll found that due to restrictive opioid measures, 56 percent (xx) of patients with serious illnesses said their doctor indicated that treatment options were limited by laws, guidelines, or insurance coverage exclusions. Over a quarter (xx) of American cancer patients and survivors acknowledged that they could not receive an opioid prescription for their pain because a pharmacist refused to fill it. Similarly, over 30 percent (xx) of cancer patients and survivors experiencing chronic pain could not receive opioid medicine as their insurance plan refused to cover it. The swift changes to the prescribing guidelines also posed a threat to patients with sudden tapering, as those cut off from opioid pain management were left with potential physical and mental agony resulting in a heightened risk of suicide (xxi). A number of experts (xxii) believe the protocols also allowed insurers to force changes in care that were not clinically safe for pain patients.

It is estimated that since the 2016 CDC guidelines were issued, most states altered their prescribing laws. Approximately 40 states (xxiii) enacted laws that limit the length of initial opioid restrictions, and 11 states have statutes capping the daily allowable dose. Most state implementing these laws did permit for exceptions particularly for those with cancer and palliative care. Despite several exceptions for certain conditions those with chronic or intractable levels of pain without an oncology diagnosis or specified disease were left with limited exceptions. Even among states attempting to address such high levels of pain with exceptions, the 2016 guidelines continue to deter practitioners from engaging in the treatment of these patients.

In 2019, the CDC acknowledged (xxiv) that some policies and practices attributed to the initial guidelines were inconsistent with its recommendations. Rather than be an intended roadmap for clinicians navigating the complexities of pain management, the guidance measures were misapplied and improperly considered a set of rigid rules, according to federal officials. To rectify circumstances, the Center put forth newly proposed guidance in 2022 that would enable better access for those facing chronic and intractable pain, emphasizing individualized patient-centered decision-making. The proposal from the agency no longer lists specific limits on the dose/duration of an opioid prescription and promotes a best judgment practices approach among clinicians. This move is seen by pain management advocates as a step in the right direction and should be worth closely monitoring by stakeholders as it makes its way through the rules process.

STATE ACTIONS

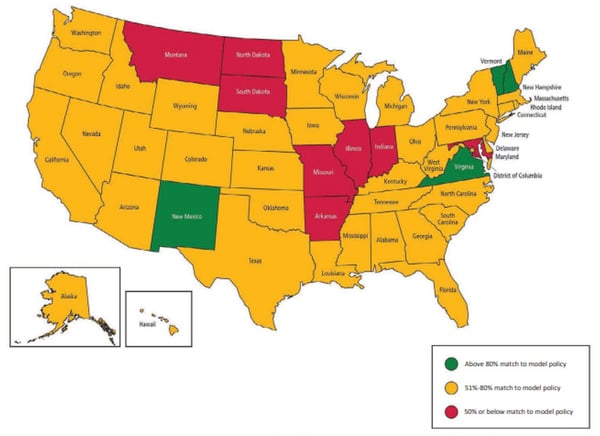

2018 Pain Policy in the States

American Cancer Society Pain state rankings in accordance with access, regulation, and attention to patient's pain needs.

Most states and their agencies require the treatment of those going outside of traditional opioid guidance to be documented, tracked, and closely monitored by a physician. To help pain management patients attain access to their medical needs, several states have passed legislation at the state level. In 2022 alone, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island took comprehensive steps to ensure those with chronic pain could receive and seek out appropriate treatments.

State definitions of intractable pain differ from state to state, with some of the first intractable and chronic pain exemption statutes appearing in the 1990s in California and Texas. Most states identifying intractable levels of pain agree on the common theme that it is a pain that cannot be treated under traditional routes. Some states may list the conditions excluded from conventional opioid guidance, as seen in Oklahoma and Arizona. In contrast, others like Minnesota and Florida may only require that the individual seeking treatment broadly meet the state's definition of intractable pain rather than have a specific condition. There is also the chance that certain requirements, such as the number of days supply, may be waived as seen in Alaska, Hawaii, and New York.

States also may add protections for physicians when prescribing for intractable pain patients in good faith, as seen in:

With more states turning their attention to making exceptions for those facing remarkably painful circumstances, regulators and prescribers still notice the stigma and misinterpreted profile opioid use brings, exposing another barrier to care. A recent decision from the U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS) may help modify such stigma and alleviate physician concerns for prescribing to chronic and intractable pain patient groups. The rare unanimous ruling from the Supreme Court in Ruan V. U.S. will now require prosecutors charging physicians with illegal prescription practices at the federal level to prove criminal intent in such cases. This recent decision brings protection to doctors who prescribe in good faith to best mitigate their patient's high-level pain and prosecute those who actively engage in deceitful prescription protocols. Justice Alito summed up the court's line of thought stating "A doctor who makes negligent or even reckless mistakes in prescribing drugs is still 'acting as a doctor' — he or she is simply acting as a bad doctor. The same cannot be said, however, when a doctor knowingly or purposefully issues a prescription to facilitate 'addiction and recreational abuse." U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) officials have already dropped some cases since the ruling and received acquittals in other cases that went to court due to the decision.

As it stands, medical experts and pain management advocates emphasize that opioids in pain management can be approached from a balanced perspective. Rules and regulation of opioids, such as refill restrictions and pill count limits for the general population, is and remains a good policy, preventing opioids from getting into the wrong people's hands. At the same time, restricting opioids to a one-size fits all blanket policy could potentially endanger those with chronic pain levels from receiving suitable treatment that meets their medical needs.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

As it stands, medical experts and pain management advocates emphasize that opioids in pain management can be approached from a balanced perspective. Rules and regulation of opioids, such as refill restrictions and pill count limits for the general population, is and remains a good policy, preventing opioids from getting into the wrong people's hands. At the same time, restricting opioids to a one-size fits all blanket policy could potentially endanger those with chronic pain levels from receiving suitable treatment that meets their medical needs

Auspicious new remedies are on the horizon for injured workers, only increasing treatment options for those hurt on the job. Accompanied with tools such as Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) in each state, injured workers, stakeholders, and regulators hold the proper tools to limit medications to only to those who medically require them. Inventions in pain management techniques continue to exhibit tremendous potential and will hopefully one day be able to substitute more traditional methods. In its present state, the field of pain management, while making necessary advancements, may need to steer course for those facing impediments in care here and now. Patient populations experiencing chronic and intractable pain, as diagnosed by a physician, are becoming a more prominent factor when designing opioid legislation to ensure unnecessary suffering does not occur. Institutions such as the Mayo Clinic (xxv), U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (xxvi), along with a number of states, have called for an equilibrium of sorts in approaches to opioid management and to provide exemptions for those facing high pain levels in order to live a dignified quality of life.

A MESSAGE FROM THE PHARMACY

Chronic pain is a global issue of concern impacting patients in all parts of the world. Chronic pain is not only a multifactorial disorder, but also a complex public health issue with heavy physical, emotional, and societal implications. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 22% of primary care patients report persistent pain, and some studies suggest that the prevalence of chronic pain ranges from 10% to 55%. In the United States, 1 in 5 adults suffers from chronic pain, and 1 in 14 adults reports having their daily life or work activities highly impacted by chronic pain. These impacts are reflected in health costs, including direct medical costs, loss of productivity, and disability. The cost of chronic pain treatments is considered to be higher than those for other chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease, and diabetes combined.

In Australia, 20% of patients reporting chronic pain are receiving worker’s compensation (WC) benefits. This may imply that there is an association between work-related injuries and long-term pain. For workers' compensation patients, chronic pain can have an even greater clinical complexity. Injured workers often have poor clinical and functional outcomes due to delays in treatment, distress, and other complications caused by the worker’s compensation system itself.

Occupational musculoskeletal injuries are among the most frequently reported type of injury in workers’ compensation claims. While not considered a first-line option, opioids are commonly used in the treatment of such injuries. As of 2009, opioid pain medications accounted for about one-quarter of all workers’ compensation pharmacy costs. With the growing use of opioids in workers’ compensation injuries comes mounting concerns about potential misuse, dependency, diversion, and overdose. It is, therefore, important to understand which patient populations would benefit most from opioid therapy and which patients would benefit most from other therapy options.

While there is evidence that the use of opioids can aid in providing short-term pain relief, there is limited evidence to support their long-term benefits. Opioid use has not definitively shown improved functional outcomes, a primary concern in workers' compensation. Alternatively, in the workers’ compensation system, patients with multiple pain complaints, anxiety, depression, or other psychiatric comorbidities, evidence suggests that chronic opioid therapy can be reasonably effective when other therapies fail. The success of long-term opioid use relies on patient-specific factors including careful selection of medication. These patients should also receive routine and close monitoring to assess for adherence and pain improvement, to quickly identify potential misuse and help reduce inappropriate opioid prescribing.

Although opioid prescribing in the United States declined since 2012, the country still faces a high volume of opioid prescribing and use. The CDC Guidelines on Pain Management released in 2016 provided guidance that led to an accelerated decreases in overall opioid prescribing, high-dose opioid prescribing, and the concurrent prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines. Many states have since enacted new laws, regulations, and policies regarding opioid prescribing based on these guidelines. Even as the 2016 CDC Guidelines resulted in significant changes, they failed to adequately address alternate treatment options and unique patient populations.

To better address these topics, the CDC released a draft version of an update to the 2016 guidelines. As the final version is pending, the updated guidelines as presented seem to comprehensively cover chronic pain patients who either rely solely on opioids or high doses of opioids to treat their symptoms. In addition, the updated CDC Guidelines better address advancing evidence-based pain management for first-line options, such as the use of nonopioid pain treatments and non-pharmacological therapies to improve the lives of people living with pain.

Among nonopioid treatment options, anticonvulsants (gabapentinoids), antidepressants (benzodiazepines and SNRIs), muscle relaxants, analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) agents are more widely available to treat pain. Analgesics such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, are considered first line agents due to their efficacy and less serious adverse effects. Muscle relaxants are also considered first-line options, but it is important to note that one particular muscle relaxer, carisoprodol, should be avoided or carefully monitored when taken in combination with opioids. Carisoprodol has central nervous system depressant properties and can increase the risk of respiratory depression if used with opioids.

In addition to their use as anticonvulsants, gabapentinoids also have analgesic, and anxiolytic properties making them an effective option for pain management. Gabapentin and pregabalin have been increasingly prescribed as alternatives to opioids leading to concerns regarding adverse effects when misused. Some adverse effects associated with gabapentinoids include blurred vision, cognitive effects, sedation, weight gain, dizziness and peripheral edema. Gabapentinoids also raise the risk of respiratory depression and overdose when used in combination with opioids, particularly in high doses (gabapentin ≥ 900 mg/day and pregabalin ≥ 300 mg/day). When taking a gabapentinoid and an opioid concommitantly, patients should be monitored to determine efficacy and assessed to identify signs of adverse reactions, misuse, and risk of overdose.

Antidepressants and muscle relaxants are also recommended as an adjuvant therapy in cases where patients also have depression and/or muscular tension. Injured workers usually experience distress which can lead to increased rates of mental disorders. Benzodiazepines and SNRIs are most commonly recommended to treat depression and anxiety. SNRIs such as duloxetine, may cause adverse effects such as nausea and sedation. Patients should be counseled appropriately prior to initiating SNRIs to fully understand that it may take several weeks of continued use to see the therapeutic effects of these medications. Similar to other medications discussed, benzodiazepines present an elevated risk for serious adverse effects, including, respiratory depression, when prescribed concomitantly with opioids, and patients should be appropriately monitored and assessed.

Topical products, such as capsaicin, topical diclofenac, and lidocaine patches are also effective options for pain management. In general, topicals are used as adjuvant therapies and may improve quality of life. While evidence is limited, the use of capsaicin and lidocaine patches can provide a small improvement in pain severity and function for patients that present with neuropathic pain, and. topical diclofenac can be a helpful adjuvant in patients with fibromyalgia.

The use of medical cannabis to treat chronic pain remains controversial with limited evidence. Cannabis treatment remains a considerable option for work‐related health conditions that are unresponsive to conventional medical treatments or patients with difficult‐to‐manage health conditions, but is associated adverse effects such as dizziness, nausea, and sedation.

Most importantly, the revised recommendations focus on the importance of multimodal therapy and a multidisciplinary approach to promote integrated pain management. A multidisciplinary health care team should include behavioral health specialists, such as social workers or psychologists, pharmacists, nurses, and doctors working in a collaborative approach. Research studies have shown that non-drug therapies including exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), meditation, relaxation, music therapy, virtual reality, yoga, acupuncture, massage, manipulation/mobilization, and physical modalities are effective to treat chronic pain and may improve functional outcomes. Not only are these interventions more cost-efficient,– they also result in greater benefits for patients when applied alone or as adjuvants to pharmacological therapy or standard care.

Given the multifactorial aspects associated with chronic pain, it is essential to provide holistic management with a patient-centered care focus. Following a thorough patient assessment, the development of a treatment plan should encompass the consideration of patient values and preferences, the potential benefits and risks of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment options, and health systems, payers, and governmental programs that make the full spectrum of evidence-based treatments accessible to patients.

REFERENCES

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2022, April 28). A look at workplace deaths, injuries, and illnesses on Workers’ Memorial Day. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2022/a-look-at-workplace-deaths-injuries-and-illnesses-on-workers-me

- National Safety Council (NSC). (2020). Workplace Injuries by the Numbers. Retrieved from: https://www.nsc.org/workplace/resources/infographics/workplace-injuries-by-the-numbers

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). (2017, July 28). Age Adjusted Percentaged of Adults Aged 18 Years Who Were Never in Pain, in Pain Some Days, or in Pain Most Days or Every Day in the Past 6 Months, by Employment Status – National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6629a8.htm?s_cid=mm6629a8_w

- Cleveland Clinic. (2021, September 9). Chronic Pain. Retrieved from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4798-chronic-pain

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2022). What is Pain? Retrieved from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/chronic-pain.

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). (2020 November). Chronic Pain and High-impact Chronic Pain Among U.S. Adults 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db390.htm

- Silvestro S., Bramanti P., Trubiani O. & Mazzon E. (2020, January 19). Stem Cells Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury: An Overview of Clinical Trials - National Library of Medicine (NIH). Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7013533/

- Thumula V., Liu T., & Wang D. (2022 June). Interstate Variations and Trends in Workers’ Compensation Drug Payments 2018Q1 to 2021Q1 – Workers’ Compensation Research Institute (WCRI). Retrieved from: https://www.wcrinet.org/reports/interstate-variation-and-trends-in-workers-compensation-drug-payments-2018q1-to-2021q1a-wcri-flashreport

- California Workers’ Compensation Insitute (CWCI). (2021, March 10). CWCI Study Examines California Workers Comp Pharmaceutical Trends. Retrieved from: https://www.cwci.org/press_release.html?id=825

- Thumula V. & Liu T. (2021, August 26). Topical Analgesics Use in Workers’ Compensation – WCRI. Retrieved from: https://www.wcrinet.org/reports/topical-analgesic-use-in-workers-compensation

- Boenke K., Litinas E, & Clauw D. (2016, March 19). Medical Cannabis Use Is Associated With Decreased Opiate Medication Use in a Retrospective Cross-Sectional Survey of Patients With Chronic Pain – Journal of Pain (NIH). Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27001005/#affiliation-1

- Minnesota Department of Health., (2019, April 8). Medical cannabis reduces severity of symptoms for some patients with cancer, according to new study. Retrieved from: https://www.health.state.mn.us/news/pressrel/2019/cannabis040819.html

- Keehbauch J. & Rensbery M. (2015, November 15). Effectiveness, Adverse Effects and Safety of Medical Marijuana – Loma Linda University School of Medicine. Retrieved from: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2015/1115/p856.html

- Kea I. (2022 July). Uncovering Medical Marijuana in Workers’ Compensation - Injured Workers Pharmacy (IWP). Retrieved from: https://www.iwpharmacy.com/uncovering_medical_marijuana_in_workers_compensation?hsCtaTracking=8db5401e-df5e-4297-8891-942d9b88b279%7Cc5ff3d2d-74ab-4f2c-b96d-2e416192a042

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) & Center for Disease Control (CDC). (2019, January 30). Opioids in the Workplace: Data. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/opioids/data.html#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20workers%27%20compensation,declined%20from%2055%25%20since%202012.

- Mueller K., Wang D., & Lea R. (2020, September 8). The Timing of Physical Therapy for Low Back Pain: Does It Matter in Workers’ Compensation? Retrieved from: https://www.wcrinet.org/reports/the-timing-of-physical-therapy-for-low-back-pain-does-it-matter-in-workers-compensation

- Muller K., Wang D. & Lea R. (2021, September 14). Outcomes Associated with Manual Therapy for Workers with Non-Chronic Low Back Pain - WCRI. Retrieved from: https://www.wcrinet.org/reports/outcomes-associated-with-manual-therapy-for-workers-with-non-chronic-low-back-pain

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). (2016, March 18). CDC Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pian. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm

- National Pain Advocacy Center (NPAC). (2022). Harm to Patients Today. Retrieved from: https://nationalpain.org/issues#opioids-and-pain

- American Cancer Society. (2018 August). Achieving Balance in State Pain Policy. Retrieved from: https://www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/National%20Documents/Pain-Report-Card-2018-accessible.pdf

- Lovejoy T. (2018, November 19). Opioid Tapering/ Discontinuation: Implications for Self-Directed Violence and Managing High Risk Patients in the Context of Suicide Prevention - Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care (CIVIC) VA Oregon Health Care System. Retrieved from: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/3538-notes.pdf

- Stone, W. (2022, April 9). CDC weighs new opioid prescribing guidelines amid controversy over old ones – National Public Radio (NPR). Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2022/04/09/1091689867/opioid-prescribing-guidelines-pain

- C. (2022, March 1). States Likely to Reists CDC Proposal Easing Opioid Access – PEW Research. Retrieved from: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2022/03/01/states-likely-to-resist-cdc-proposal-easing-opioid-access

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). (2019, April 24). CDC Advises Against Misapplication of the Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/s0424-advises-misapplication-guideline-prescribing-opioids.html

- Mayo Clinic. (2021, January 9). Chronic Pain: Medication decisions. Retrieved from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/chronic-pain-medication-decisions/art-20360371

- S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (2019, May 9). Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report. Retrieved from: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf

PHARMACY CITATIONS

- Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Raj PP, Racz GB. Evolution of interventional pain management. Pain Physician. 2003;6(4):485-494.

- Manchikanti L, Singh V, Kaye AD, Hirsch JA. Lessons for Better Pain Management in the Future: Learning from the Past. Pain Ther. 2020;9(2):373-391. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00170-8

- Newton-John TR, McDonald AJ. Pain management in the context of workers compensation: a case study. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2(1):38-46. doi:10.1007/s13142-012-0112-0

- Sehgal N, Colson J, Smith HS. Chronic pain treatment with opioid analgesics: benefits versus harms of long-term therapy. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(11):1201-1220. doi:10.1586/14737175.2013.846517

- Duarte R, Raphael J. The pros and cons of long-term opioid therapy. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2014;28(3):308-310. doi:10.3109/15360288.2014.943383

- Dembe A, Wickizer T, Sieck C, Partridge J, Balchick R. Opioid use and dosing in the workers' compensation setting. A comparative review and new data from Ohio. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55(4):313-32. doi:10.1002/ajim.21021

- Howard J, Wurzelbacher S, Osborne J, Wolf J, Ruser J, Chadarevian R. Review of cannabis reimbursement by workers' compensation insurance in the U.S. and Canada. Am J Ind Med. 2021;64(12):989-1001. doi:10.1002/ajim.23294\

- Mathieson S, Lin CC, Underwood M, Eldabe S. Pregabalin and gabapentin for pain. BMJ. 2020;369:m1315. Published 2020 Apr 28. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1315