Pharmacy Choice White Paper

Introduction

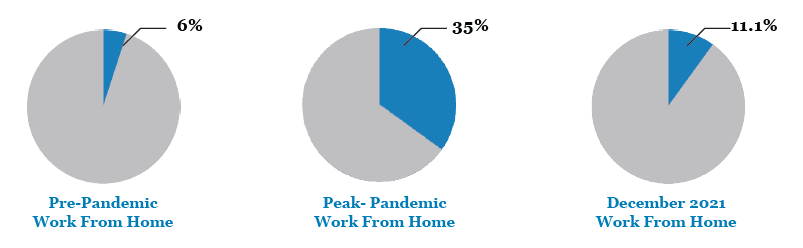

Interruptions from the pandemic continue to push the U.S. workforce from the office to home desk stations. Once a popular trend, work from home (WFH) is now the standard for many job sectors in the American economy. Before the pandemic, approximately 6%i of U.S. workers conducted the bulk of their work from home. At the pandemic’s peak in May of 2020, this went up to 35%ii. In December of 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that 11.1%iii of workers are staying home to fulfill their job duties full-time due specifically to Covid. However, the amount of those working from home in total or hybrid is significantly higher, with estimates ranging from 20-25%.

The pandemic created a myriad of new challenges, including the great resignation. From January through November of 2021 over 38 millioniv workers quit their jobs, primarily womenv. Quitting rates varied depending on the state. In the late months of 2021, AK, WY & GA recordedvi the highest quit rates between 4-5%, whereas CA, MA, MD, NY, PA, WA saw the lowest quit rates with less than 2.5%. While reasons for quitting differ for each individual, the Department of Labor suggestsvii most workers are leaving positions due to low pay, lack of flexibility, Covid health concerns, and lagging childcare options.

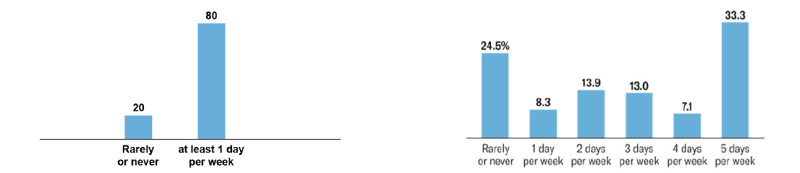

How often do workers want to work from home?

Nearly 80% of U.S. employees want to work from home at least one day each week, according to a monthly survey of more than 10,000 Americans conducted between May 2020 and July 2021. After Covid, in 2022 and beyond, how often would you like to have paid workdays at home?

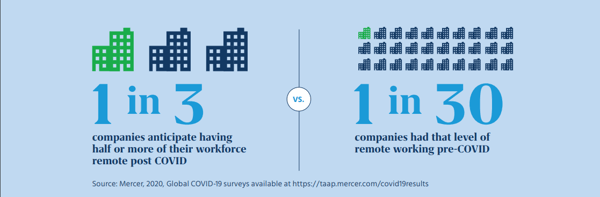

In response, employers are offering WFH and hybrid options to many employees to help employees keep safe, rebalance the work-life scale and retain workers. WFH arrangements are becoming so popular that nearly 50%viii of workers that worked remote during the pandemic say they would take up to a 5% pay cut to continue to work remotely in some capacity according to a recent national survey. Some forecasts say that by 2025 36.2 million Americans will be at home for work permanently, approximately a quarter of the total workforce. The future of work is at home, and it’s clear that a number of workers are drawing a line in the sand to make sure that’s the case.

With WFH becoming increasingly normalized, workers and employees will likely face questions about new arrangements. One topic that is currently grappling legislators, lawyers, and the workers’ compensation industry is the matter of WFH injuries. When commuting to and from work, most workers are ineligible for benefits based on coming and going rules. Due to this precedent, workers may believe they can only be eligible for workers’ compensation benefits when in the office physically. However, this is not the case.

In general, WFH injuries are compensable regardless of location, and employers continue to be required to hold workers’ compensation insurance. WFH injuries do encounter a series of complications based on the circumstances of each case and overall, the burden of proof remains on the employee. The subject is already addressed in some case law and since Covid harnessing discussions in legislative circles.

The most common WFH injuriesix include slips, trips, and falls accompanied by cumulative injuries. Those injuries labeled as cumulative usually indicate poor ergonomics at the workstation; consequently, back pain and carpal tunnel syndrome can be frequent issues for home office workers. Several employers are permitting workers a stipend for office setups for preventive purposes to counter these injuries. Company initiatives to allocate home office funds or provide equipment signals that WFH setups are here to stay and that workers should understand what does and doesn’t constitute an at-home injury for workers’ compensation.

Employees need to be aware that proving the injury occurred in the home is largely the employee’s responsibility. It should also be known that workers’ compensation presumptions, laws, or regulations that presume an injury or illness is contracted through one’s work are overall not applicable to WFH injuries. Any injury occurring in the home will be subject to if the employee can prove the injury occurred.

Demonstrating that an injury happened is an arduous ordeal and can be difficult for injured workers. States will usually require documentation of a 911 call, a doctor’s visit following the injury, or a witness that can attest to the events. To ensure a claim holds validity proving the injury occurred within the home is the first step. Workers hurt at home while carrying out work-related activities need to ensure that they have documented the injury to the best of their ability.

Legal Precedent

Is the worker working from home engaging in work-related activities at the time of their injury? This question is the standard regarding WFH injuries. Printing off a work document and tripping on your living room rug while en route would likely be considered a compensable injury. However, leaving one’s desk to do laundry and stumbling in the process may be regarded as a personal task, thus ineligible for workers’ comp benefits.

The Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) section 1904.5(b)(7)x states that “injuries and illnesses that occur while an employee is working at home, including work in a home office, will be considered work-related if the injury or illness occurs while the employee is performing work for pay or compensation within the home. The injury or illness (must be) directly related to the performance of work rather than to the general home environment or setting.” OSHA’s definition does provide guidance, though the interpretation of this rule fluctuates among the states.

Most states do not have exact statutory language around whether WFH injuries are eligible for workers’ compensation

While the pandemic pushed some states to better address this discrepancy, it is yet to be seen whether states will decisively clarify through legislative action. Due to a lack of clarity, most states lean on their courts for answers on WFH injuries. Through coming and going rules, commuting to and from work is not considered engaging in work-related activity, and therefore, no coverage is given in the event of an incident. Specifically, the worker is not rendering any service to the employer and as such would not be considered “on the job.” Whereas WFH setups follow a different set of principles such as a.) the home as a second office and the b.) personal comfort doctrine.

When employers require or allow an employee to WFH the office setup within the residence is usually considered a secondary job site. With such designation, the same benefits and protections at work apply to the home. Take the case of Verizon Pennsylvania v. the Pennsylvania Workers’ Compensation Appeal Board (2006)xi, where an employee working from home fell walking down the staircase to answer a ringing phone call for work. As the employee attended to their job duties within the home, the court sided with the injured worker. The employee descending the stairs to answer a work phone and falling in the process met the criteria for attending to their job duties within the home.

Secondary Job Site Principle

A recent state appellate ruling in 2020, Capraro v. Matrix Absence Management et al. the NY Workers’ Compensation Boardxii xiv, in New York, confirmed the secondary job site principle. Matrix Management allowed their employee to WFH, giving them a computer for work purposes. However, the company did not provide reimbursement for office furniture. Due to this, the employee ordered his own office needs. Outside of work hours, the employee went to bring the packaged office supplies inside from being delivered, in doing so, injuring their back. Initial rulings denied the claim as it did not arise out of and in the scope of employment, referring to the carrying of the furniture as a personal matter only. The appellate court reversed this decision citing the employer’s computer setup within the employees’ home created a secondary work site. Further, the court deemed the office equipment ordered by the employee as “sufficiently work-related,” making the claim compensable.

A recent state appellate ruling in 2020, Capraro v. Matrix Absence Management et al. the NY Workers’ Compensation Boardxii xiv, in New York, confirmed the secondary job site principle. Matrix Management allowed their employee to WFH, giving them a computer for work purposes. However, the company did not provide reimbursement for office furniture. Due to this, the employee ordered his own office needs. Outside of work hours, the employee went to bring the packaged office supplies inside from being delivered, in doing so, injuring their back. Initial rulings denied the claim as it did not arise out of and in the scope of employment, referring to the carrying of the furniture as a personal matter only. The appellate court reversed this decision citing the employer’s computer setup within the employees’ home created a secondary work site. Further, the court deemed the office equipment ordered by the employee as “sufficiently work-related,” making the claim compensable.

Personal Comfort Doctrine

Another line of thought is the personal comfort doctrine. Through this view, most states accept that an employee is given some level of personal comfort in their work duties, such as using the bathroom or grabbing food/drink. The Verizon V. Pennsylvania WC Appeal Board ruling concluded that the personal comfort doctrine also applied since the employee went to the kitchen to grab water strengthening the injured workers argument.

Another line of thought is the personal comfort doctrine. Through this view, most states accept that an employee is given some level of personal comfort in their work duties, such as using the bathroom or grabbing food/drink. The Verizon V. Pennsylvania WC Appeal Board ruling concluded that the personal comfort doctrine also applied since the employee went to the kitchen to grab water strengthening the injured workers argument.

The personal comfort doctrine also extends to breaks and non-work hours in some instances, as seen in Minnesota with the case of Munson v. Wilmar/Interline Brandsxiii. The employee on a Saturday fell down the stairs with a cup of coffee attempting to return to their workstation to print off work documents; the court saw this claim as eligible for workers’ compensation.

The personal comfort doctrine also extends to breaks and non-work hours in some instances, as seen in Minnesota with the case of Munson v. Wilmar/Interline Brandsxiii. The employee on a Saturday fell down the stairs with a cup of coffee attempting to return to their workstation to print off work documents; the court saw this claim as eligible for workers’ compensation.

However, A similar 2019 case in Floridaxiv, Sedgwick CMS and The Hartford/Sedgwick CMS vs. Tammitha Valcourt-Williams did not receive a favorable ruling. The employee went to the kitchen to grab a cup of coffee, tripping over their dog in the process. The court determined that “it is reasonable to conclude that the claimant who is permitted to work from her home would go to her kitchen on breaks,” establishing the employee is entitled to some reasonable comfort when performing job duties at home. Unfortunately, the dog being present within the home hindered the employee’s argument. The injury would have likely been eligible for compensation without a canine presence involved.

However, A similar 2019 case in Floridaxiv, Sedgwick CMS and The Hartford/Sedgwick CMS vs. Tammitha Valcourt-Williams did not receive a favorable ruling. The employee went to the kitchen to grab a cup of coffee, tripping over their dog in the process. The court determined that “it is reasonable to conclude that the claimant who is permitted to work from her home would go to her kitchen on breaks,” establishing the employee is entitled to some reasonable comfort when performing job duties at home. Unfortunately, the dog being present within the home hindered the employee’s argument. The injury would have likely been eligible for compensation without a canine presence involved.

“Arising out of and in the scope of employment” is a common term when attempting to decipher WFH injury eligibility. For the Sedgewick/Hartford CMS v. Valcourt-Williams ruling, the employee did suffer an injury arising out of their work environment since the employee is authorized to WFH. Alas, the court stated the employee did not experience the injury while conducting their job duties or “in the scope of employment,” referring to time and place. The dog being in the home is not a similar hazard as at the physical workplace; thus, the injured worker does not qualify for benefits.

Authorization

Authorization is another crucial element to WFH claims, as seen in a 2018 workers’ compensation claim by a Texas Department of Family & Protective Services caseworker (Martinez v. State Office of Risk Management)xv. The worker in this case reached for a pen from the other side of her kitchen table, in the process falling, resulting in a broken shoulder and a hit to the head. The court believed that the employee’s actions were “furthering the business and affairs” of her employer. Nonetheless, the employee did not receive permission to WFH. Along with working on a Saturday, violating the Texas wage and hour laws, the court determined the injury non-compensable.

Authorization is another crucial element to WFH claims, as seen in a 2018 workers’ compensation claim by a Texas Department of Family & Protective Services caseworker (Martinez v. State Office of Risk Management)xv. The worker in this case reached for a pen from the other side of her kitchen table, in the process falling, resulting in a broken shoulder and a hit to the head. The court believed that the employee’s actions were “furthering the business and affairs” of her employer. Nonetheless, the employee did not receive permission to WFH. Along with working on a Saturday, violating the Texas wage and hour laws, the court determined the injury non-compensable.

WFH injuries cannot be evaluated the same with different precedents and interpretation in each state

For example, precedent in Illinois allows for more WFH injuries to be compensable than Missouri, where case law is more stringent to bar WFH injuries from compensability. Illinois courts have consistently found that the employers’ lack of control over an employee’s environment within the home is irrelevant towards the injury and that only a lower level of proof be necessary to be a compensable injury.

For example, precedent in Illinois allows for more WFH injuries to be compensable than Missouri, where case law is more stringent to bar WFH injuries from compensability. Illinois courts have consistently found that the employers’ lack of control over an employee’s environment within the home is irrelevant towards the injury and that only a lower level of proof be necessary to be a compensable injury.

In contrastxvi, Missouri statutes strictly define what constitutes an injury eligible for workers’ compensation. The state definitions say that a WFH injury is not eligible if the hazard or risk is unrelated to employment per 287.020xvii. The personal comfort doctrine would be less applicable to Missouri state laws by this definition. A Missouri court would likely deny the claim if someone tripped over their dog or spilled hot coffee on themselves. Though hurting oneself by reaching for a work document or turning on the work computer would present more validity to a claim. Missouri’s narrow interpretation would likely make it more challenging for claimants to become eligible for a WFH claim.

In contrastxvi, Missouri statutes strictly define what constitutes an injury eligible for workers’ compensation. The state definitions say that a WFH injury is not eligible if the hazard or risk is unrelated to employment per 287.020xvii. The personal comfort doctrine would be less applicable to Missouri state laws by this definition. A Missouri court would likely deny the claim if someone tripped over their dog or spilled hot coffee on themselves. Though hurting oneself by reaching for a work document or turning on the work computer would present more validity to a claim. Missouri’s narrow interpretation would likely make it more challenging for claimants to become eligible for a WFH claim.

While most states adhere to similar principles and doctrines, state statutes can throw a caveat into a workers’ compensation case. In the Carolinas, South Carolina subscribes to a more straightforward and more standardized test to deem compensable injuries by applying “arose out of and in the course of employment.”

While most states adhere to similar principles and doctrines, state statutes can throw a caveat into a workers’ compensation case. In the Carolinas, South Carolina subscribes to a more straightforward and more standardized test to deem compensable injuries by applying “arose out of and in the course of employment.”

In North Carolina, the same standard applies with the addition of “the result of an accident” in Chapter 97xviii of the state statutes. This addition to the state’s standard can exclude illnesses and certain diseases as the definition could be construed to strictly physical injuries. There is a wide range of case law and precedents to consider for WFH injuries. Cases are evaluated on their own merits and particulars. With more employees working from home, the case-law of one’s specific state can be vital to handling their claim status.

In North Carolina, the same standard applies with the addition of “the result of an accident” in Chapter 97xviii of the state statutes. This addition to the state’s standard can exclude illnesses and certain diseases as the definition could be construed to strictly physical injuries. There is a wide range of case law and precedents to consider for WFH injuries. Cases are evaluated on their own merits and particulars. With more employees working from home, the case-law of one’s specific state can be vital to handling their claim status.

Legislation/Regulations for WFH Injuries

Despite worries that workers’ compensation claims would spike during the Covid pandemic, claims overall declinedxix. Regardless, some states are considered restricting their eligibility rules for WFH injuries. Although case law is the primary navigator of workers’ compensation WFH injuries, a few states are looking to amend their state statutes and definitions.

In Ohio, lawmakers are seeking to address WFH injury qualifications through the legislature. HB447 proposed in 2021 and reintroduced in 2022 would exempt WFH injuries from workers’ compensation. The bill does provide certain exceptions if the following conditions are met: The injury or disability arises out of the employee’s employment. The employment necessarily exposes the employee to conditions that substantially contribute to the risk of injury or disability. Or if the injury/disability is sustained in the course of an activity undertaken by the employee for the exclusive benefit of the employer.

In Ohio, lawmakers are seeking to address WFH injury qualifications through the legislature. HB447 proposed in 2021 and reintroduced in 2022 would exempt WFH injuries from workers’ compensation. The bill does provide certain exceptions if the following conditions are met: The injury or disability arises out of the employee’s employment. The employment necessarily exposes the employee to conditions that substantially contribute to the risk of injury or disability. Or if the injury/disability is sustained in the course of an activity undertaken by the employee for the exclusive benefit of the employer.

The proposed Ohio bill tightens the scope of WFH injuries. In effect, the bill could reduce the amount of workers’ compensation claims by creating more strict guidelines for workers’ compensation eligibility. Ohio’s proposed bill is unique, with most states not following suit.

WFH injury compensability has not garnered significant interest from state legislators. Instead, some states delegate this duty to their workers’ compensation boards to create standards and rules to expand or limit eligibility for such injuries. California, for example, provides a webpage dedicated to guidance on WFH for employers and employees. While legislative changes and regulatory rules can provide a pathway for understanding WFH injuries, case law will continue to be crucial to deeming compensability.

Employers will need to be closely involved with WFH guidelines, as seen with Martinez v. State Office of Risk Management in Texas and in New York with Capraro v. Matrix. Rules set forth by companies on WFH safety standards and job duties allowed to be performed can prevent injuries. Stipends and or issuing proper office furniture/equipment can also reduce a company’s liability for a claim. Clear-cut policies on when WFH should be conducted and the hours its limited to should also be considered.

Conclusion

Remote work is a new standard in today’s economy. With Covid still labeled in a pandemic stage, workers with remote capability will need to utilize the home office when exposure or contraction of the virus occurs. WFH will be permanent for a sizeable amount of the American workforce and employers need to be prepared to accommodate the public health crises and the demands of the labor market. WFH is still in its infancy stages with a plethora of benefits for both employees and employers. By offering WFH opportunities, employers are experiencing cost savings with less need for large office space and travel. Remote work is also improving workflow while simultaneously increasing employee retention. Meanwhile, employees benefit from reduced commute times, financial savings on fuel, and a reinvigorated work-life balance approach. Even so, WFH arrangements present consequences that employees, employers, regulators, and legislators should continue to consider.

Determining eligibility will ultimately depend on numerous factors. WFH injuries can be trickier to make a claim on than other injuries in the physical workplace. Workers need to ensure they can prove their injury occurred at home before proceeding with a WFH claim. Employees should check their state’s laws, regulations, and case law to see if their claim would be compensable in the state they work.

Sources

i. Coate, Patrick. (2021, January 25). Remote Work Before, During and After the Pandemic – National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI). Retrieved from: https://www.ncci.com/SecureDocuments/QEB/QEB_Q4_2020_RemoteWork.html.

ii. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Supplemental data measuring the effects of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic on the labor market. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/cps/effects-of-the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic.htm.

iii. Kaplan, Juliana & Kiersz, Andy. (2021, December 8). 2021 was the year of the quit: For 7 months, millions of workers have been leaving. – Business Insider. Retrieved from: https://www.businessinsider.com/how-many-why-workers-quit-jobs-this-year-great-resignation-2021-12

iv. Pardue, Luke. (2021, November 12). A real-time look at the great resignation – Gusto. Retrieved from: https://gusto.com/company-news/a-real-time-look-at-the-great-resignation

v. McAnn, Adam. (2022, January 21). 2022 States with Highest Job Resignation Rates – WalletHub. Retrieved from: https://wallethub.com/edu/states-with-highest-job-resignation-rates/101077#video’

vi. Kaplan, Juliana. (2022, January 27). 3 Reasons Everyone is Quitting Their Job, According to Biden’s Labor Secretary – Business Insider. Retrieved from: https://www.businessinsider.com/3-reasons-everyones-quitting-great-resignation-biden-labor-secretary-2022-1.

vii. Owllabs. (2021). State of Remote Work 2021. Retrieved from: https://owllabs.com/state-of-remote-work/2021/.

viii. Hallo, Steve. (2021, August 12). The most common work form hoe injuries – PropertyCasualty360 Magazine. Retrieved from: https://www.propertycasualty360.com/2021/08/12/the-most-common-whf-injuries/

ix. Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA). (2022). Determination of work-relatedness – U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved from: https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1904/1904.5

x. Verizon Pennsylvania Inc. V. Workers’ Compensation Appeal Board (Alston). (1804 C.D. May 31, 2006).

xi. Capraro v. Matrix Absence Management, 187 A.D.3d 1395 (3d Dept., Oct. 22, 2020).

xii. Gary Munson V. Wilmar/Interline Brands & St. Paul Travelers. (Workers’ Compnesation Court of Appeals No. WC08-025, December 16, 2008.)

xiii. Sedgwick CMS and The Hartford/Sedgwick CMS v. Tammitha Valcourt-Williams. (District Court of Appeals Florida, First District, 271 So.3d 1133 2019).

xiv. Edna A. Martinez v. Texas State Office of Risk Management. Appeal, 37th Judicial District Court of Bexar County. (No. 04-14-00558-CV, November 7, 2018).

xv. MVP Law. (2021, April 1). Are Remote Workers’ Injuries Compensable? Retrieved from: https://mvplaw.com/are-remote-workers-injuries-compensable/.

xvi. Missouri Statutes Title XVIII Labor & Industrial Relations, Chapter 287.020. Retrieved from: https://revisor.mo.gov/main/OneSection.aspx?section=287.020

xvii. North Carolina Statutes Chapter 97 Workers’ Compensation Act Article I. Retrieved from: https://www.ncleg.net/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/HTML/ByArticle/Chapter_97/Article_1.html

xviii. Wise, Carolyn & Fernes, Kevin. (2021, November 30). Workers’ Compensation Frequency and Severity, What’s Covid Got To Do With It – NCCI. Retrieved from: https://www.ncci.com/Articles/Pages/Insights-WorkersComp-Frequency-Severity-COVID.aspx